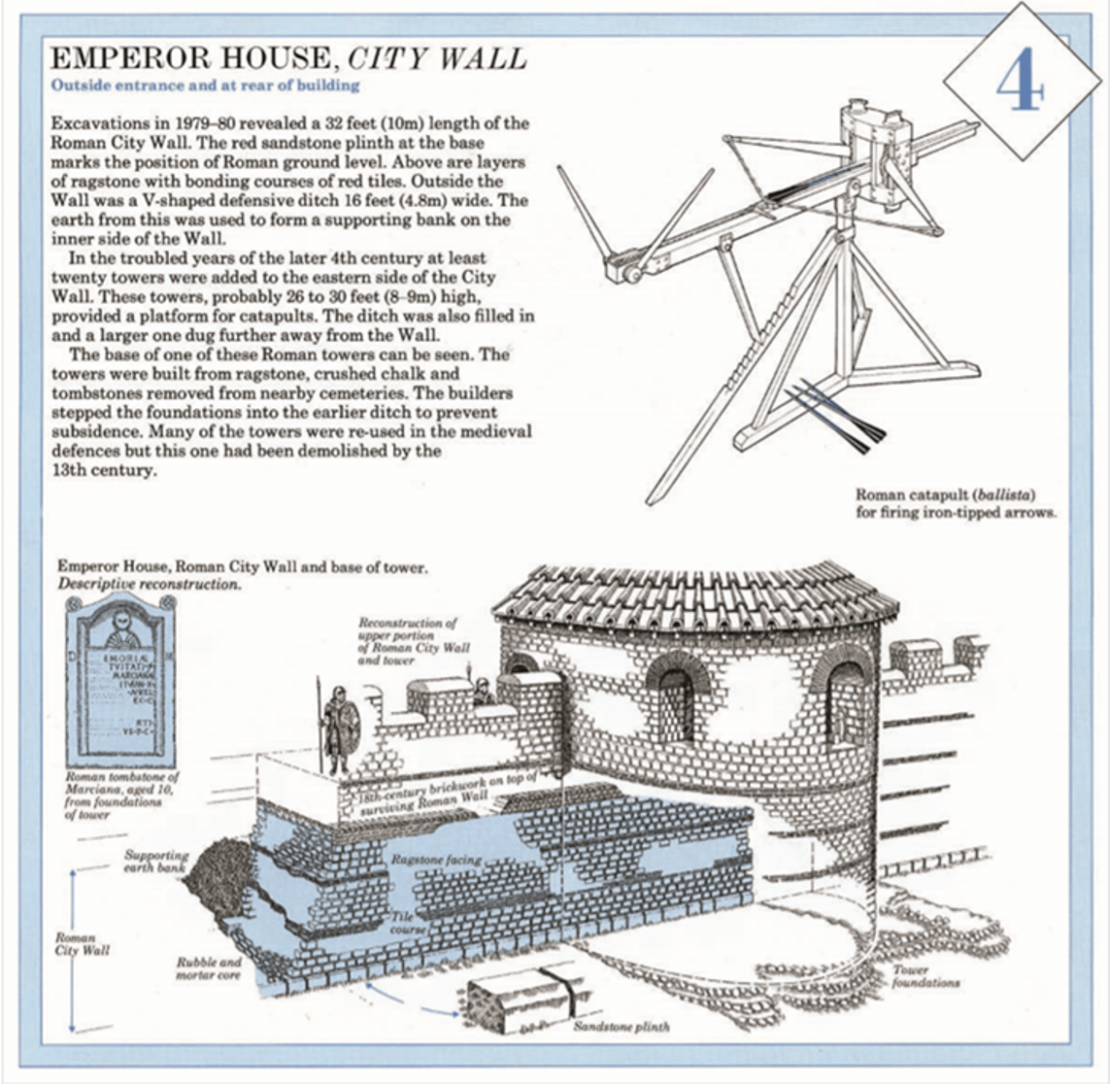

Although the exact date of construction is unknown, archaeological evidence suggests that the original Roman Wall of London was built at some point between AD 190 and AD230 and it would have been a major logistical challenge.

London is built on natural clay and at the time there were bountiful supplies of wood but no convenient supply of stone. It is estimated therefore that around 1 million blocks of stone were bought up the Thames Estuary from Kent to build the wall which would have stood up to 6 metres high and 3 metres wide. Each side of the wall was faced with grey Kentish ragstone, and the interior was filled with rubble and concrete. Above the ragstone are the very distinctive red clay tile courses which were put in at intervals to strengthen and level the wall and which are a key indicator of Roman masonry in London.

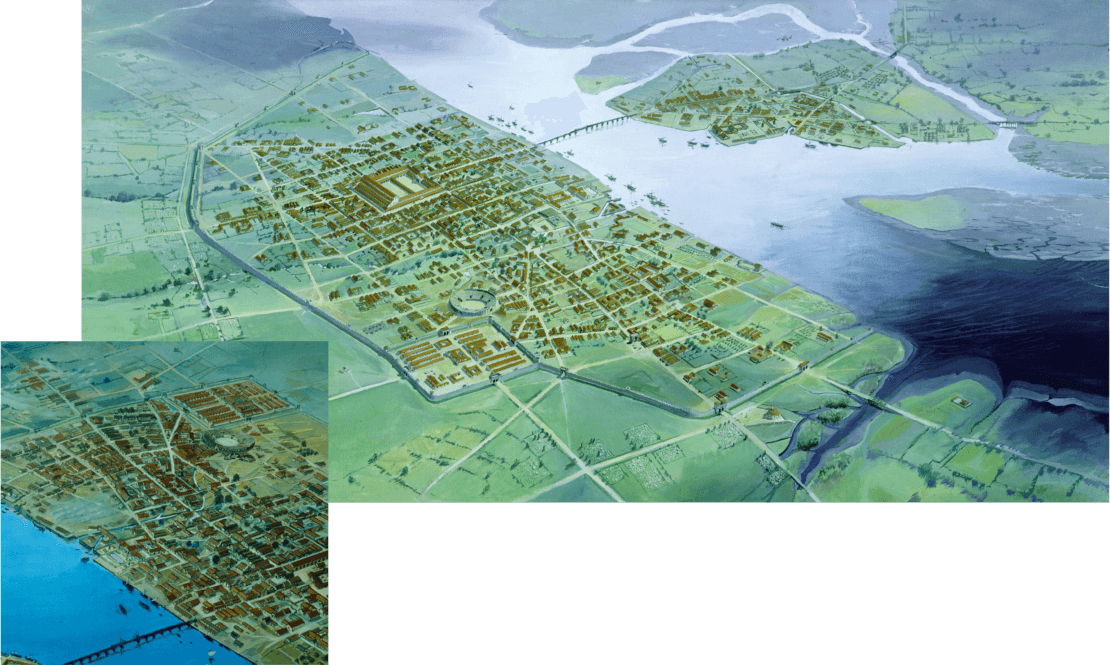

The finished wall was about 3.2 km long and followed the original boundary line of Londinium which at its peak was home to a population of around 25,000 people from across Britain and Europe.

THE

BASTION

Another typically Roman feature visible at the City Wall at Vine Street are the stepped, chalk foundations of the bastion (or defensive tower), one of several built up against the eastern wall in the 4th century.

As of today, this is the only remains of a Roman bastion in London and in its heyday it probably looked something like it does in this illustration. It is thought that this particular bastion lasted until it was pulled down, or fell down, in the medieval period.

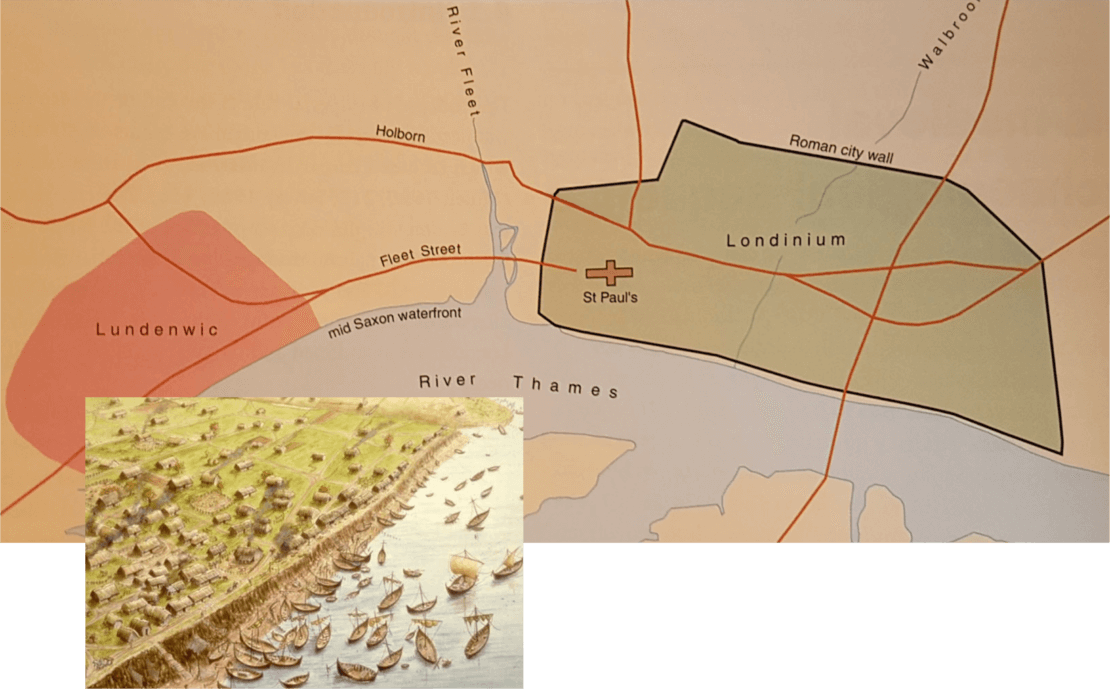

After the Romans

In the early 5th century, Britain and Rome parted company. By this time, Londinium was a gated community of high-ranking officers and officials of Rome. When Rome withdrew, they had no reason to stay and by the middle of the 5th century Londinium was deserted. The buildings fell in on themselves. The wall was no longer maintained and started to crumble. Everything was overgrown. The Saxons who moved into the area created other settlements, the most significant of which was Lundenwic, located where Covent Garden is now.

Although a successful trading settlement, Lundenwic was susceptible to Viking attacks, and it was King Alfred that re-populated the fortified city, repairing the wall and so retaining the shape of the original Roman City which in turn became the shape of the medieval city of London, when further repairs and enhancements to the wall were carried out.

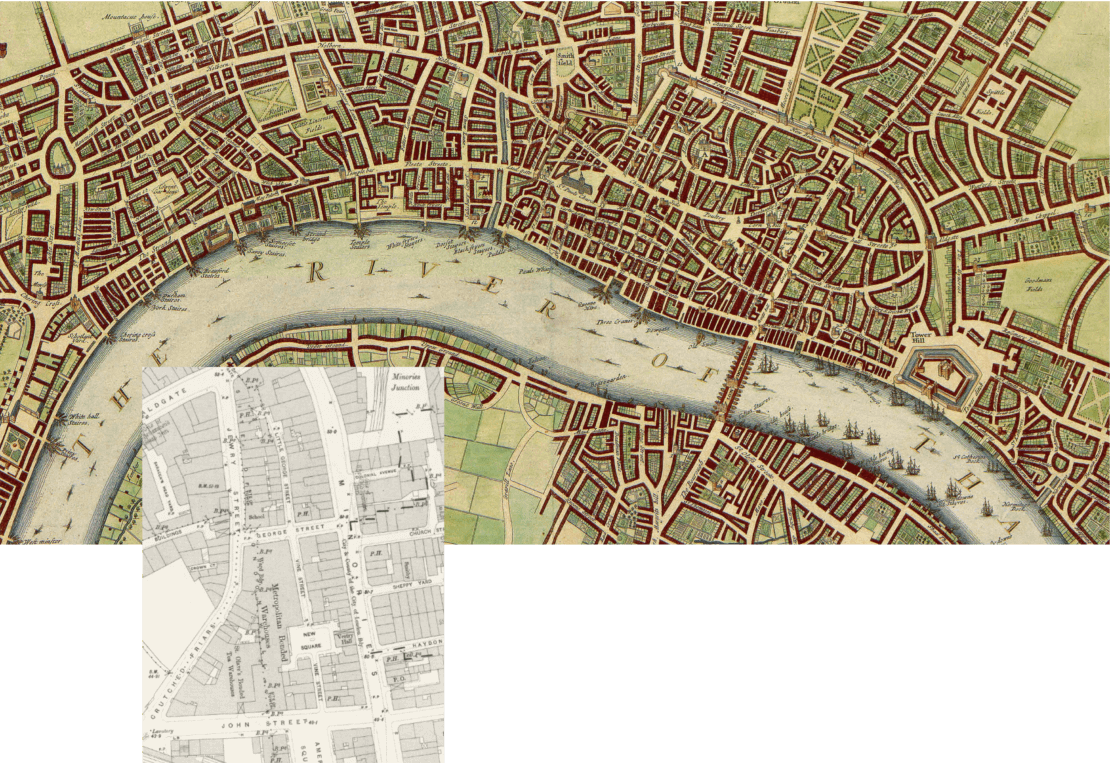

From 1600

By the 1600s the City had expanded beyond the wall. Glass and metal-working workshops were prevalent around Vine Street and by the 1700s residential buildings also appeared outside of the wall. These were replaced in time by warehouses which dominated the local skyline in the 19th century and rapid development resulted in the wall in this area being built over until it was finally uncovered in 1979 but with no public access.

Over the years it has been a defensive structure, a status symbol, a party wall and even a means of raising revenue. Now it is a monument and the central focus of an exhibition and is set to survive to bear witness to the next 1800 years.